As a neuroscience and health enthusiast, I have spent years researching how to optimize productivity, energy, and longevity. My typical day includes getting up at 6:30 am, hopping in an outdoor ice bath for the brown fat and dopamine, getting sunlight in my eyes and on my skin for cortisol and testosterone, and fasting until 4 pm for autophagy. My bowl is usually a colorful combination of purple rice, carrots, kale, and guacamole.

When talking about health – especially diet – a disclaimer is in order, and I’m not talking about the “I’m not a doctor” kind. Rather, I’m talking about the “everyone is different” kind. Diet has been one of the most hotly debated topics since we started eating things: even Adam and Eve were given diet advice they eventually broke.

Here is the general principle: we all need to be our own scientists to determine what kind of diet helps us achieve our desired cognitive outcomes, whether it be focus, energy, and productivity.

Even within my own timeline, I’ve experimented with Keto, vegetarian, and a high-meat diet. I’ve tried eating every few hours, eating large breakfasts, and only eating dinner. The most interesting part is, I can probably find good peer-reviewed research defending each of those diets.

So how can I possibly be writing about which foods enhance dietary performance to the general public? The answer is, while we don’t know what will work for everyone, there are good practices most people can follow when it comes to eating for cognitive performance. In this article, I use peer-reviewed research to outline what those principles are.

A Healthy Diet

If you open most nutrition textbooks, one of the first principles you learn is the components of a healthy diet. These are variety, adequacy, balance, and moderation (Davis & Serrano, 2016). You may also learn about the general dietary guidelines for Americans that were established based on a large body of evidence. Generally, a healthy diet is high in vegetables, fruits, whole grains, low-fat or nonfat dairy, seafood, legumes, and nuts; lower in red and processed meats; and low in sugar-sweetened foods and drinks and refined grains. Given our busy lives and limited budgets, most people don’t just stumble into this kind of diet. What is accessible and convenient is usually the most processed, sugary, or high in saturated fats. Food that is considered healthy is usually physically far away, unaffordable, or out of the skill range of many to prepare.

In Food and Nutrition Economics: Fundamentals for Health Sciences, Davis and Serrano report that the average American eats far too many saturated fats, sweets, and refined grains and far too few fruits and vegetables. In fact, they report that less than 33.6% of individuals follow all of the FDA dietary recommendations. What does this do to cognitive performance?

Brain Fog: Poor nutrition means decreased performance.

A good place to start exploring the answer is through a meta-analysis, a study analyzing data from multiple studies looking at food and cognitive performance. Nutrition and Performance at School is an example of a meta-analysis published in 2005 that showed how a deficiency in micronutrients (essential nutrients found in fruits, vegetables, and meat) decreased academic performance. The analysis also showed that iron deficiency therapy programs immediately improved academic performance. For populations that were severely undernourished, breakfast programs improved academic performance as well (Taras, 2005).

We can draw a few insights from these results. The fact that breakfast programs improved performance shows that sufficient calories from food was needed for success in the classroom (quantity). The fact that micronutrient deficiency was correlated with poor academic performance means that what was eaten was equally important for cognitive performance (quality).

Digging deeper into individual studies, we can begin to answer the question of what kind of diet improves cognitive performance.

Quantity

In one study, researchers gathered food frequency scores from over 6000 elementary school children in Korea and looked at their GPAs over the course of the school year. Those that had access to regular meals achieved higher academic performance, even when controlling for the socioeconomic status of parents. (Kim et al., 2003).

Quality

In a 2008 article, Diet Quality and Academic Performance, researchers measured diet quality in 5200 school-aged children in Canada. Diet quality was measured by fruit and vegetable intake as a percentage of caloric intake from dietary fat. In other words, the more fruits and vegetables the person ate compared to dietary fat, the higher their dietary quality measurement. The authors then looked at scores on standardized literacy tests. Can you guess what the correlation was? Yes, higher diet quality was associated with better performance on the test (Florence et al., 2008).

You can find many other studies with similar findings as the ones above. So what’s the common theme? A diet sufficient in fruits and vegetables is correlated with better academic performance, and I don’t think it would be too much of a stretch to transfer this correlation to cognitive work in general.

Getting There From Here

So we have a target for how to eat for cognitive performance: get high-quality fresh food in sufficient quantity. But how do we get there from here?

Whenever health economists think about nutritional interventions to improve health outcomes, they think about the following relationships (Davis & Serrano, 2016).

- Budget-Food: how your budget affects the food you buy.

- Preference-Food: how your preferences affect the food you buy.

- Food-Nutrient: how the food you eat affects the nutrients you consume.

- Nutrient-Health: how the nutrients you consume affect your health.

In the case of the Food-Budget relationship, subsidies and assistance programs incentivize healthier food purchases. As for the Preference-Food relationship, health education is guiding our preferences toward healthy foods (Forbes). As we continue to learn about how nutrients affect our health, we can further refine the conversation about healthy nutrition (Food-Nutrient and Nutrient-Health).

But what about access?

Time, money, and location still prevent many Americans from accessing the nutrition they need to thrive.

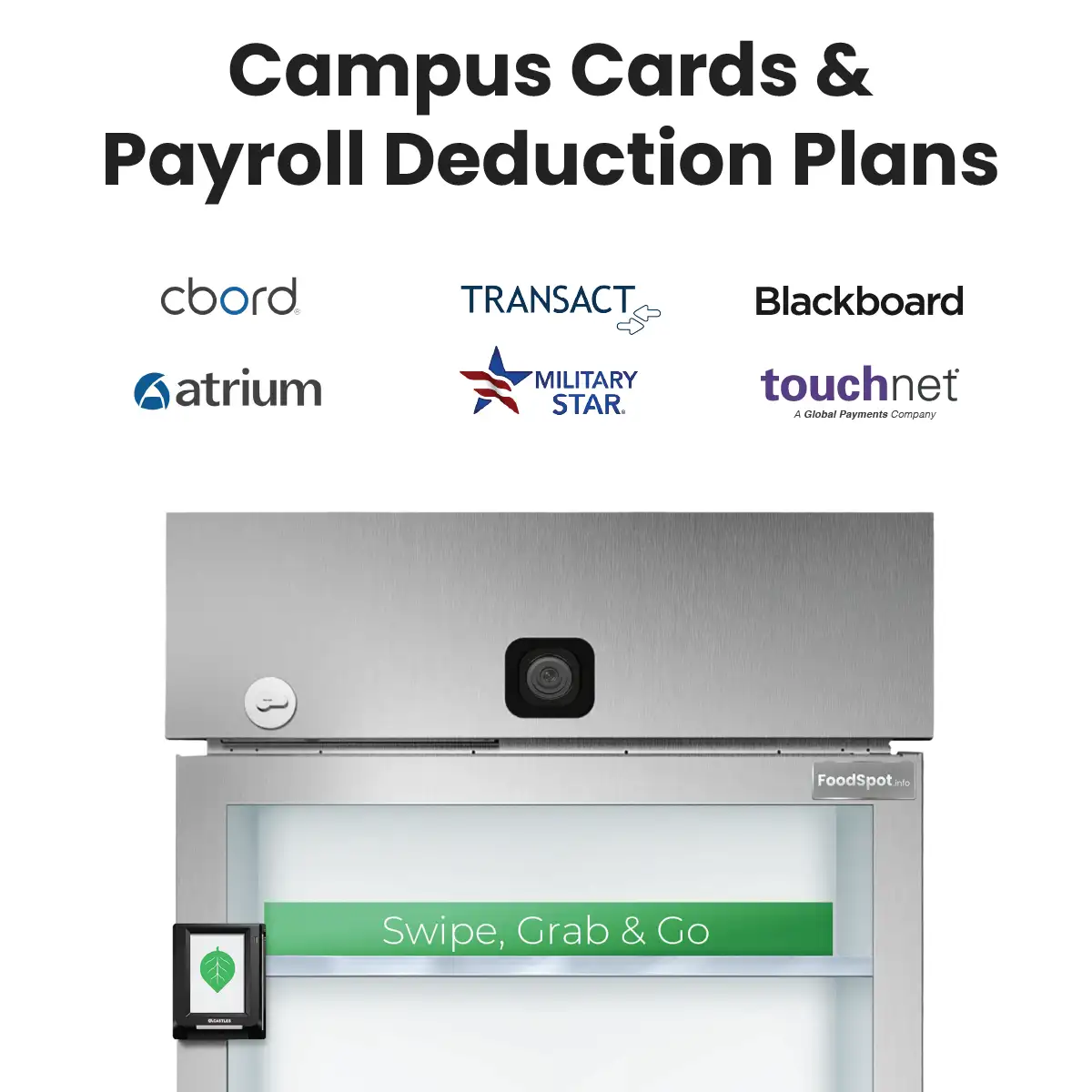

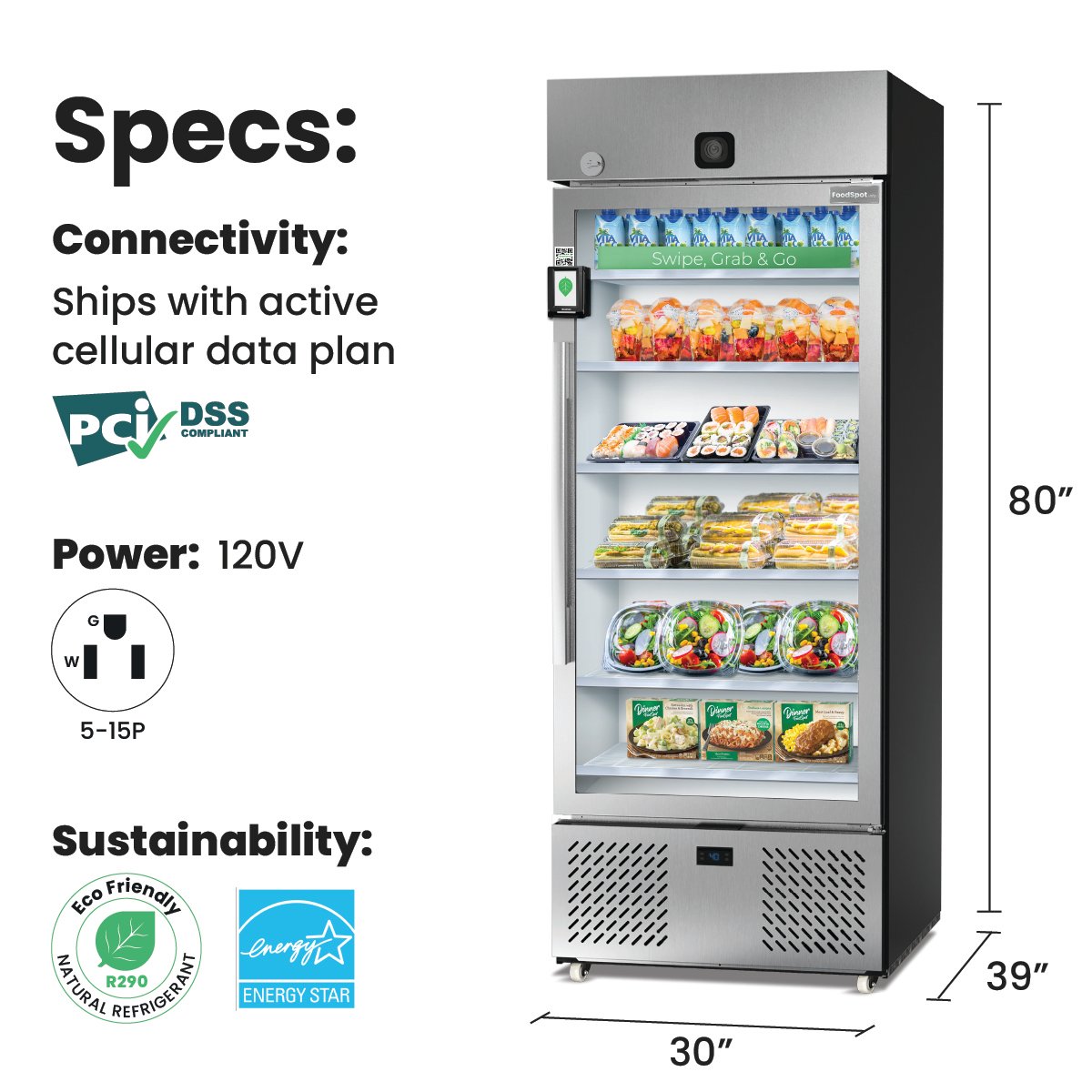

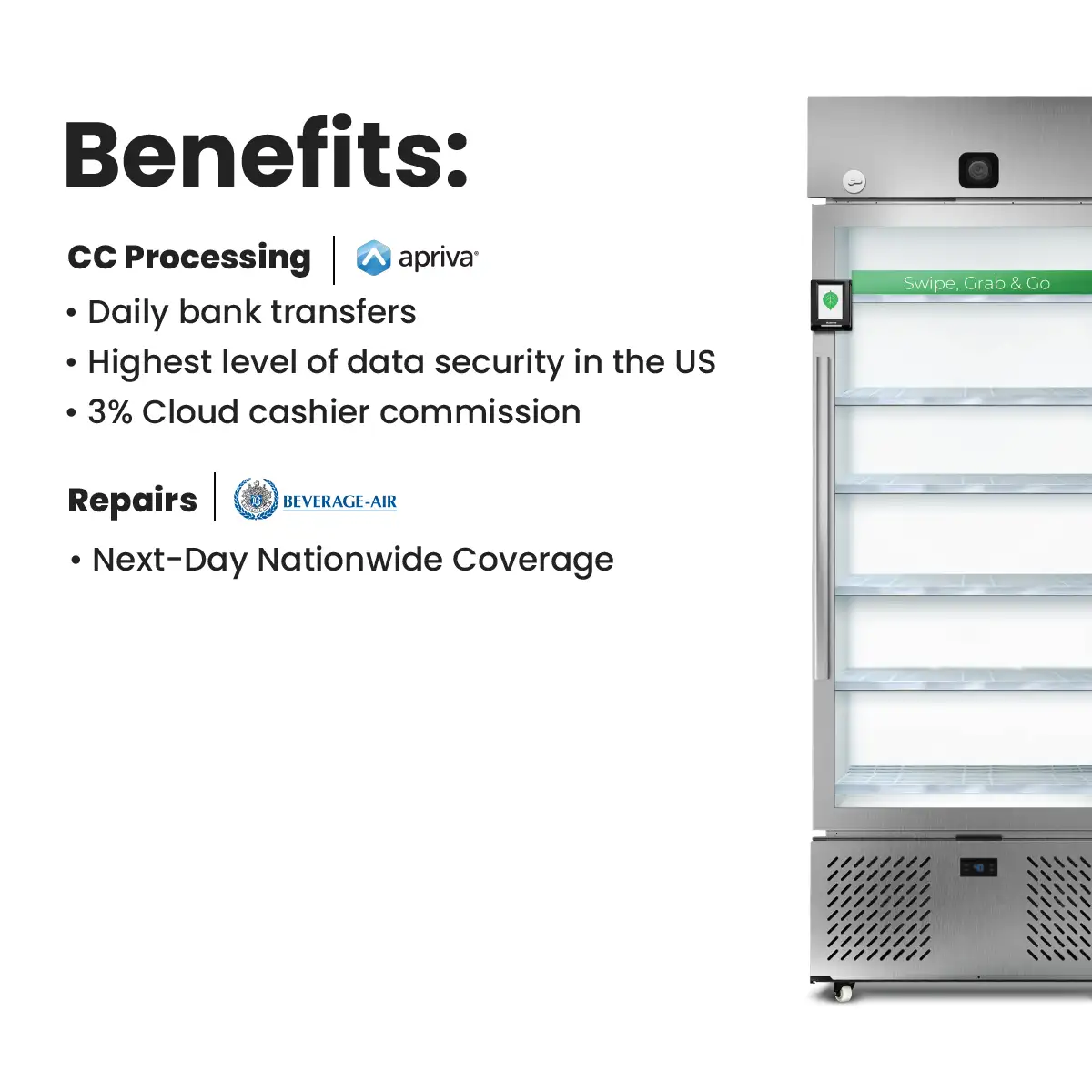

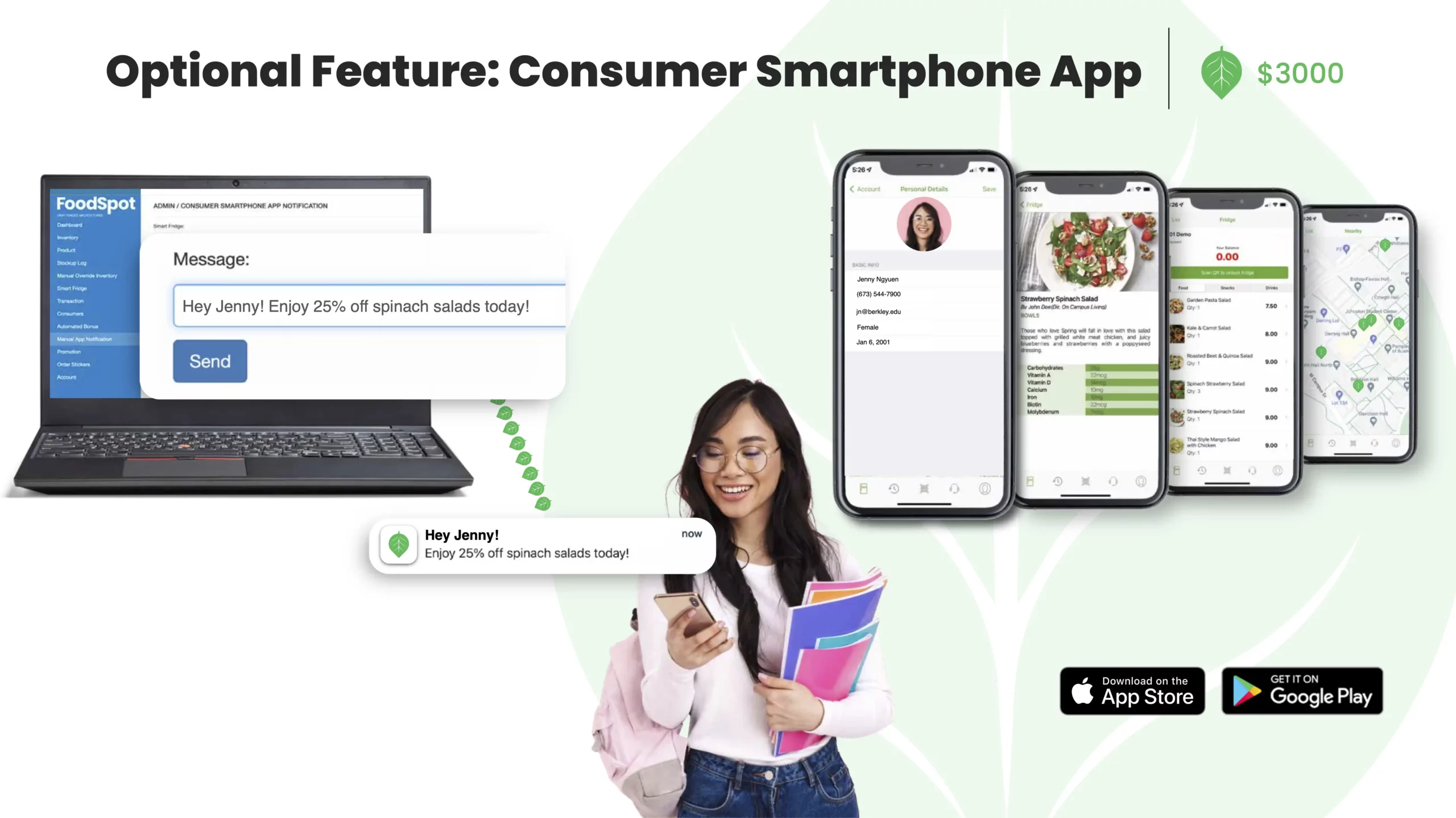

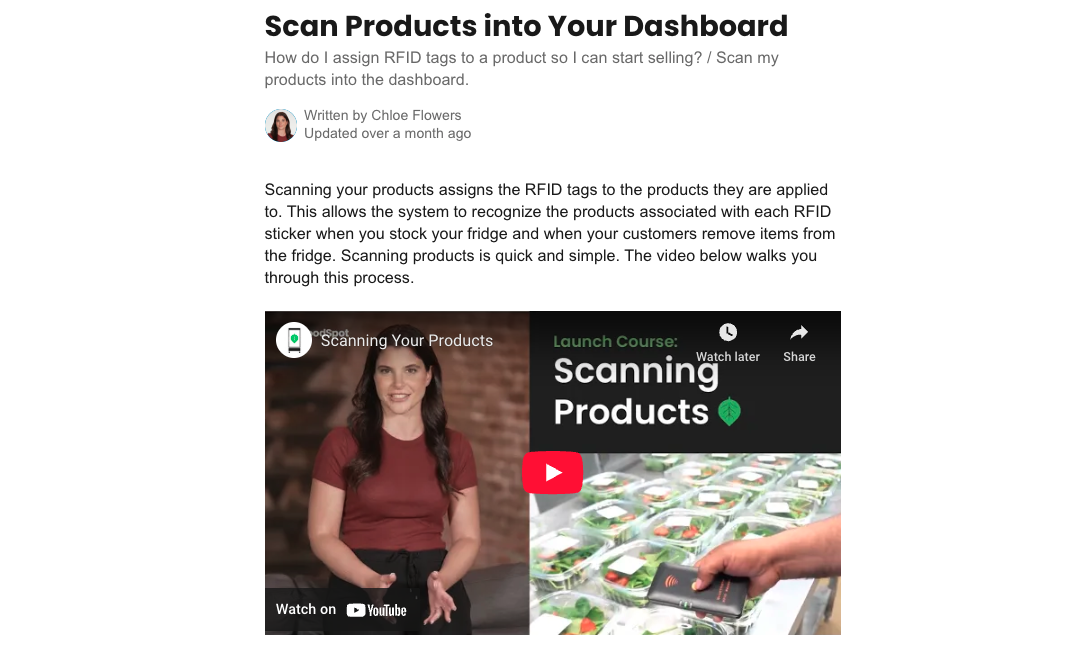

At FoodSpot, we are fulfilling our vision of high-quality fresh food accessibility for all by creating 24/7 fresh food oases in underserved areas. Our technology allows anything from salads to sushi to be sold from our smart fridges. Smart inventory tracking allows per-item expiration and food safety information to be viewable from an online dashboard, empowering operators sell high quality fresh food 24/7 with no onsite labor.

Our food pantry-centered operators allow multiple vendors to stock their fridge with fresh food, perhaps that is nearing the end of its life. It can then be sold for a discounted price or fully subsidized to the most vulnerable populations in the community. In this way, we are unlocking high-quality nutrition for populations that need it most. We are replacing the Budget-Food problem with food equity.

If you see a need on your campus or in your community, we would love to work with you. Please reach out at hello@launchfoodspot.com.

References

Davis, G. C., & Serrano, E. L. (2016). Food and Nutrition Economics: Fundamentals for Health Sciences. Oxford University Press.

Florence, M. D., Asbridge, M., & Veugelers, P. J. (2008). Diet Quality and Academic Performance*. Journal of School Health, 78(4), 209–215. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00288.x

Fontani, G., Corradeschi, F., Felici, A., Alfatti, F., Migliorini, S., & Lodi, L. (2005). Cognitive and physiological effects of Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation in healthy subjects. European Journal of Clinical Investigation, 35(11), 691–699. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2362.2005.01570.x

Hu, Y., Hu, F. B., & Manson, J. E. (2019). Marine Omega‐3 Supplementation and Cardiovascular Disease: An Updated Meta‐Analysis of 13 Randomized Controlled Trials Involving 127 477 Participants. Journal of the American Heart Association, 8(19), e013543. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.119.013543

Jazayeri, S., Tehrani-Doost, M., Keshavarz, S. A., Hosseini, M., Djazayery, A., Amini, H., Jalali, M., & Peet, M. (2008). Comparison of Therapeutic Effects of Omega-3 Fatty Acid Eicosapentaenoic Acid and Fluoxetine, Separately and in Combination, in Major Depressive Disorder. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 42(3), 192–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048670701827275

Kim, H.-Y. P., Frongillo, E. A., Han, S.-S., Oh, S.-Y., Kim, W.-K., Jang, Y.-A., Won, H.-S., Lee, H.-S., Kim, S.-H., & Han, S.-S. (2003). Academic performance of Korean children is associated with dietary behaviours and physical status. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 12(2).

Taras, H. (2005). Nutrition and Student Performance at School. Journal of School Health, 75(6), 199–213. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2005.tb06674.x